Lana Stojičević, Black Hill, 2015, series of photographs. Courtesy of the artist.

Irena Borić (1982) is an art historian who works as an independent curator and critic. She holds an MA in Art History and History (2009) from the Faculty of Philosophy, Zagreb and an MA in Arts and Heritage: Policy, Management and Education (2011) from Maastricht University. She lives and works in Maribor, Slovenia.

The task of this text is to weave a thread between a few art practices that (co)respond to their immediate environment, be it urban or rural, and tend to challenge our modes of being in them. As it happens, the localities in question have to do with the post-Yugoslav territory of Slovenia and Croatia, as here, my practice as a curator and critic is immersed. This essay focuses on art practices that envision disturbances in the landscape in order to expose the pressing complexities of the social, economic and political context that, due to global capitalism, surpasses its own outlines.

The problem is that “capitalism creates a unifying, artificial grounding, a master code or common language that allows objects and ideas to be compared against each other under the rules of the market. This ‘overcoding’ (Deleuze and Guattari 1987:42) is not only merging, hierarchizing and stratifying objects, ideas and individuals but is also allowing socio-political and economic problems to surface globally almost instantaneously, only to be amplified by their co-dependence on the universal Capital,”1 as Lila Athanasiadou wrote in the Posthuman Glossary. As a result, certain local issues can be quite familiar elsewhere despite the distance, as the specific causality of the local events is influenced by capitalist grounding. Perhaps in that way, the text also attempts to experiment with notions of space and time and their dearrangements as it seems that nothing is no longer affected solely by its immediate surroundings. Thus, the proposition to the readers is to get familiar with the art practices that respond to their context in order to invest their knowledge and look into discrepancies between (un)familiar localities that may be provoked by geographical distance.

Slow violence, because it is so readily ignored by hard-charging capitalism, exacerbates the vulnerability of ecosystems and of people who are poor, disempowered, and often involuntarily displaced while fueling social conflicts that arise from desperation as life-sustaining conditions erode.

The motif to start with is an element of vernacular architecture—a hayrack, an emblematic symbol of a rural landscape. A wooden structure for drying crops that is usually situated at the homestead or separately on the field or meadow has been in use for centuries, and some of its shapes are distinctive for Slovenian territory. At the same time, a hayrack is also a consequence of agricultural and livestock activities in the country, and as such, it can be seen as a human-made disturbance in the landscape, exposing the taming of nature. The landscape painter, as he proclaims himself, Staš Kleindienst, is very much aware of the connotative burden that hayrack carries, and this is why he sets it as a central motif of the painting Harbinger of the Night (2023). Strikingly, the hayrack is here, turned into a pink neon sign. The neon wrap charged the purpose of a hayrack that became an illuminating road sign, subtly reflecting the current economic climate in which rural spaces cannot escape commodification. The lack of hay from the hayrack can be read as a symptom of the transformation of a rural landscape into a commodified space. The concept of Kleindienst’s landscapes evokes the atmosphere of Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s and Hieronymus Bosch’s paintings, in which the predominant theme of landscape includes human interference. Same as in Harbringer of the Night, despite the absence of a human figure, there is a trace of human activity and this, to my understanding, comes as a disturbance that deconstructs the perception of a rural space of untouched nature (which represents an idealistic trope) or even a space that belongs to everyone. It becomes a disturbed space that, to the careful observer, speaks of the impact of the current economic imperative, which asks for economic, political and social domination over land.

Staš Kleindienst, Harbringer of the Night, 2023, oil on canvas, 45 x 35cm, private property. Courtesy of the artist.

It may seem difficult to imagine rural space as public, as it is more likely that its public aspect should also be reserved for non-human and more-than-human beings. The question of the public space in the expanded field is addressed by Danilo Milovanović in the site-specific work Outcrying the Hawkers (2023), in which hayrack is again the central carrier of meaning. The work is inspired by the impressionist painting The Sower (1907) by Ivan Grohar, an iconic work of Slovenian art history in which a hayrack is visible in the background of the sower. What inspired Milovanović was the general reception of the painting and the usage of its image for commercial and marketing purposes. Thus, the pixelated image of Grohar’s image, inserted into rural scenery, broadens the visual discrepancy between the two. The artist meticulously observes how public space shrinks and in what conditions by appropriating a hayrack in order to confront its newly found commercial usage. He responded to an increased usage of hayracks as billboard stands with the removal of a giant poster from the hayrack. Its shredded version was returned to the hayrack, in which its long strips resemble the appearance of the hay. With this action, the artist attempted to outcry the billboard as the main actor of the visual pollution. The artist took the action further by repeating it in reverse – placing the hay within the frame of the city billboard. The hay in commercially designated space in the city of Ljubljana becomes an equally strange object as a shredded billboard on a hayrack is, as each of them challenges our visual assumptions and expectations.

Danilo Milovanović, Outcrying the Hawkers, 2023, Courtesy of the artist.

Danilo Milovanović, Outcrying the Hawkers, 2023, Courtesy of the artist.

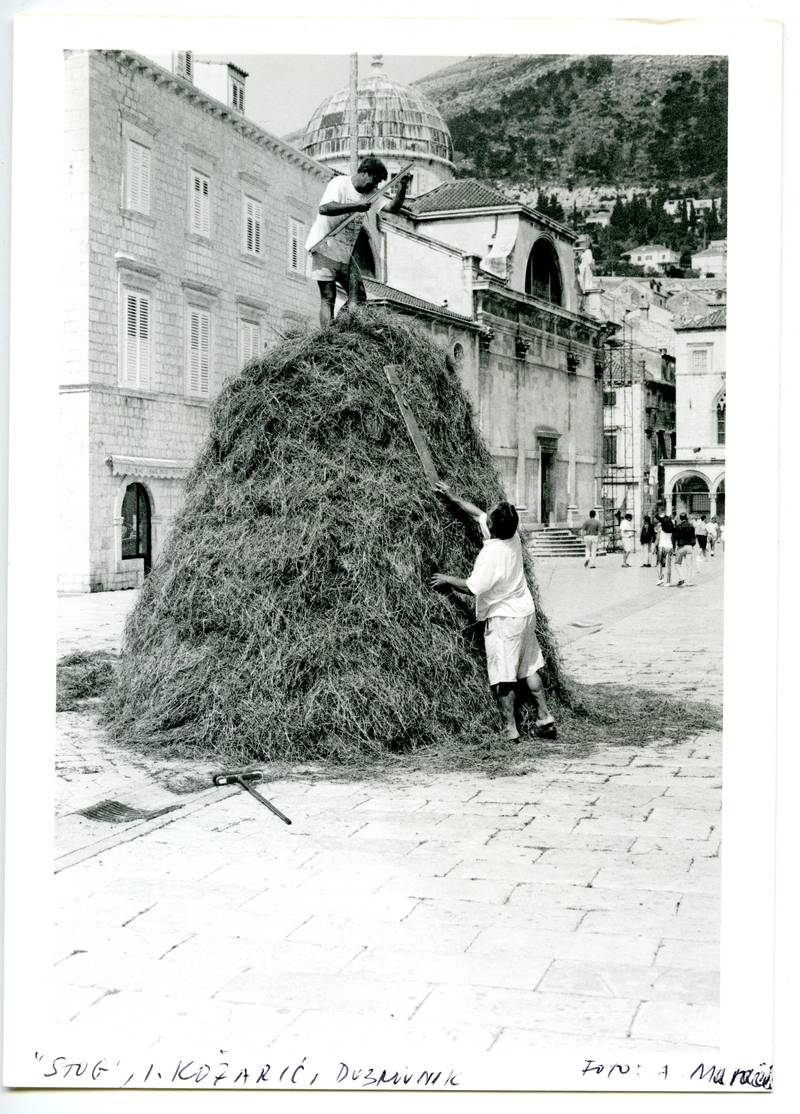

Interestingly, when ephemeral material such as hay is displaced in an urban context, all sorts of unexpected meanings are inscribed. Perhaps the confusion partially comes from its ordinariness and purposelessness. The similar gesture to Milovanović’s hay billboard we will find in Haystack (1996) by sculptor Ivan Kožarić. By installing a haystack in front of the renaissance Rector’s palace, Kožarić was mostly interested in confrontation/contrast among materials, the ephemeral nature of hay, its shape, its temporality and its smell juxtaposed to centuries-old stones of the city of Dubrovnik. As art historian Antun Maračić points out, “the installation of Kožarić’s sculpture in public space is an act of revelation, that is, of establishing the centre, of marking and activating the acupuncture point of space, of stirring up its energetic line of force.”2 While urban and rural collide, the cut out element of rural scenery in the old town functions as an element of wonder, provocation even. Due to the patronizing relation of urban towards rural, even an ordinary rural motif of a haystack in the old town appears as a foreign object.

Slow violence, because it is so readily ignored by hard-charging capitalism, exacerbates the vulnerability of ecosystems and of people who are poor, disempowered, and often involuntarily displaced while fueling social conflicts that arise from desperation as life-sustaining conditions erode.

Ivan Kožarić, Haystack, 1996. Museum of Contemporary Art Zagreb, Documentation and Information Department. Photo: Antun Maračić

A foreign element of another sort is called Black Hill, around which artist Lana Stojičević created a work Black Hill (2015) consisting of photographs, a costume, sound recording, a video and interviews. The artist departed from the actual locality that consisted of approximately 140,000 tons of potentially hazardous waste from the former Electrode and Ferroalloy Factory (TEF) in Šibenik that was 2010 dumped in the village of Biljane Donje in Croatia. Instead of being disposed of at a landfill, the slag was deposited in the middle of the village as it had been considered raw material, not waste. In spite of protests and the decision of an industry professional that the slag must be removed, the locals and the fertile area continue to be affected by it. It is an example of slow violence, as Rob Nixon defines it, the violence wrought by climate change, toxic drift, deforestation, oil spills, and the environmental aftermath of war that takes place gradually and often invisibly. Moreover, slow violence, because it is so readily ignored by hard-charging capitalism, exacerbates the vulnerability of ecosystems and of people who are poor, disempowered, and often involuntarily displaced while fueling social conflicts that arise from desperation as life-sustaining conditions erode. Lana Stojičević learned about the particular case of Black Hill through the in-depth research of the former factory that also included visits to the terrain of the factory, as well as several locations near Šibenik on which waste had been disposed of while the factory was in operation. The lack of discussion and concern within the public discourse provoked the artist to address the impact of the artificial and dangerous post-industrial landscape on the village and its residents. By imagining the black slag heaps as the surface of an unknown planet, she “exposed the strangeness of the location and highlighted the absurdity of the presence of this threatening alien body in the village”. By placing herself as a figure in such a landscape, she represents the powerless locals who wander across the Black Hill as if it were limbo. In the video, the masked figure can never quite cross the border of the hill, emphasizing the tension between the natural and artificial landscape. The artist designed the costume, combining a former folk costume and a protective suit, with the purpose of highlighting how futile protection has become. The costume is covered in a local embroidery pattern (četverokuka) that symbolizes hope and protection. Additionally, the artist conducted interviews with local inhabitants in order for their stories to expose stories of popular power, in Rebecca Solnit’s words “ stories that motivate people to do what it takes to make the world we need. Perhaps we also need to become better critics and listeners, more careful about what we take in and who’s telling it, and what we believe and repeat because stories can give power – or they can take it away.”3

Lana Stojičević, Black Hill, 2015, series of photographs. Courtesy of the artist.

OR poiesis, YAMAMAYU, 2020, visual collage for a performative walk / deep listening practice. Courtesy of the artist.

How to tell the story of a disturbed landscape differently was also of interest to artist Petra Kapš allias OR poesis in a bio-acoustic sound-research project centring on the sonority of the Japanese oak silkmoth YAMAMAYU (2020). In view of the current planetary environmental events, the project thematises the role and condition of forest habitats from the perspective of a specific species of nocturnal moths and their sensitive life cycle enabled by a healthy forest. The cyclicality and thermal diversity, as well as the presence of large temperature differences needed by high deciduous forests, are also essential for a suitable habitat for the Japanese oak silkmoth that assimilated in Slovenian deciduous forest between the middle and the end of the 19th century. Thus, annual moth populations are an indicator of the conditions in the forest and the seasonal, weather-related and atmospheric factors. As part of the project, the artist conceived a night walk into the forest in Maribor, which suddenly seemed like unknown territory. The walk was done entirely in silence in order to engage with our immediate surroundings, such as smells, noises, sounds, and shadows, through other senses than vision. The artist was interested in finding ways to listen to the invisible and how to perceive beings that do not want to be heard. Just at one point of the voiceless walk, the participants were invited to break the silence by turning on the designated earphones and carefully listening to the narrative of the sound piece. Being asserted in the landscape, the participants were encouraged to connect with nature differently, to fine-tune their senses and to hear the story of yamamayu well.

The human presence within the landscape is already some sort of disturbance, and this is painfully present in Jošt Franko’s series Keine Chance (2019-ongoing). The archive in progress is an attempt to acknowledge people on the move who “have been robbed of their lives, torn from their histories and cursed to repeatedly migrate.” Using a variety of non-linear and fragmented visual strategies, including photography, video, objects and found footage, collage and text, Keine Chance addresses the hardships as well as the impossibility of the future of asylum seekers who have found themselves trapped on the outskirts of the European Union. It documents the unruly space in between in which one is caught rather than aims to go. Unidentifiable space somewhere along the Balkan refugee route right next to the border that needs to be crossed comes out as an inescapable asylum. The images expose the temporal nature of homes in need, in which the trees unintentionally become an infrastructure of an improvised shelter. Temporal occupation is entangled with improvisation of sorts, as it uses all sorts of materials at hand. The traces of their presence, of their being in the world are functioning as waste assemblages that come out of high-intensity struggle. The items left or appropriated bear witness not just to the wasted place but also to the wasted people.

Even though there are numerous art practices that, due to the current crisis, deal with various landscape politics and poetics not only through visual language but also through activist approaches, I found these practices meaningful due to their substantial engagement.

Jošt Franko, Keine Chance, 2019-ongoing, series of photographs. Courtesy of the artist.

The connections between the aforementioned works are somewhat provisional, but I deliberately unfold the thread of disturbances in a landscape as this is the topic widely discussed on so many levels with the greatest urgency. However, the disturbances that these works are tackling are not pervading in a grandiose manner of overwhelming catastrophes that are daily broadcasted over popular media. Instead, they appear as quiet signifiers of larger issues whose complexity remains opaque. In a way, they feel similar to glitch, as a temporary broken image in which precisely this rupture holds the troublesome message. This way, the expected pattern is broken, and the artist interferes with the existing paradigm in order to challenge its meaning fragmentally. Even though there are numerous art practices that, due to the current crisis, deal with various landscape politics and poetics not only through visual language but also through activist approaches, I found these practices meaningful due to their substantial engagement. Unlike the artistic endeavors that are durational and work along the intersections of art and life, their engagement with the immediate environment is not as direct nor as permanent. Even though we are aware that behind represented matter, there is a whole process of weaved relations and connections with humans and more than human beings, this aspect is not part of the representation of the work, it remains hidden, belonging solely to the sphere of life. Whether the work as such appears as a disturbance or recognizes the disturbance, the works make us think of complex relations between different separabilities. As Vanesa Machado di Oliveira wrote: “Separations between humans and earth and other-than-human beings are premised on conquest, domination, and property ownership. Separations between human beings and human cultures occur through creation of hierarchies premised on race, ethnicity, gender, class, sexual orientation, ability, neurotypicality, nationality, employment and citizen status.”4 Thus, the cause of the disturbances are not solely the long (and invisible) limbs of a capitalist system that nothing escapes from, but also the outskirts of the discriminatory hierarchies.

At the time of writing this text, Danilo Milovanović did a simple action, Human, leave no traces in which he found a nice spot by the lake in which, next to a trash can, a bench and some litter, there was a hand-painted board with the inscription: Human, leave no traces. After he sat on a bench and enjoyed the scenery, he decided to follow the request from the board by taking away literally all human traces – the trash trowed around, the trash can, the bench and even the inscription. With this tautological exercise in a manner of conceptual art, the artist exposed precisely this human interference that is so overwhelmingly present even when it is not visible. The humorous gesture pinpoints the problematic relationship towards the environment, or earth if you will, as if humans are in fact, in control. It also gently reminds us that human beings are just an extension of the planet and not the other way around.