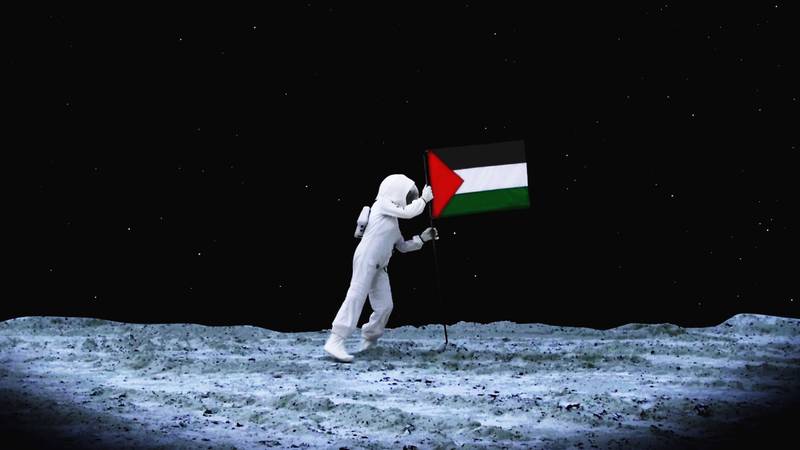

Still from Larissa Sansour & Søren Lind: As If No Misfortune Had Occurred in the Night, 2022. Image: Larissa Sansour & Søren Lind

Sanabel Abdelrahman is a bilingual writer (Arabic and English) of fiction and essays. She holds a Ph.D. in Arabic studies with a focus on Palestinian magical realism. She is interested in questions around alternative literatures, re-processing traditional figures into contemporary literature, and studying fictional and distorted spaces. Sanabel is also interested in contemporary art and film.

Israel is still bombing and starving tens of thousands of people in Gaza as I write this essay. The image of martyred souls rising to the sky has become an everyday depiction of this horrific time. It is an image that compliments an unfathomable amount of distortion, both physical and metaphysical, that continues to be inflicted upon the Palestinian people, spaces, memories, and, by extension, futures. Forced to endure such a violent present, Palestinians’ projections of the future continue to oscillate between an even drearier space and a hopeful, liberated one.

As the voices calling for Palestinian freedom intensify by the day, it benefits this critical moment to examine possible exercises in re-thinking settler-colonial and postcolonial violence while imagining alternative futures. The Palestinian struggle for a liberated future necessitates borrowing from other cultures and traditions while carving out spaces for emboldening and empowering intersectionality. With that in mind, what potentialities of hope and resistance can be encapsulated under alternative imaginings of the (Palestinian) future? Rather than compare and contrast the definitions and applications of science fiction, how can we trace the potentialities of hope and collective imagination around liberation under critical science fiction(s)? How can we understand Indigenous climate fiction as an effective tool to resist the violence of the present towards just futures?

Here, by drawing on a selection of short films from Turtle Island and Palestine, I shed light on some Palestinian and Indigenous approaches to science fiction and some of its genres in film while highlighting their power in creating popular, anticolonial, liberated futures and agencies.

In its broadest terms, science fiction is understood as fiction of the future based on scientific theory, phenomena, experience and projections. Science fiction texts “often [attempt] to anticipate the dangers of a new technology before it is even invented.”1 Such attempts at anticipation reflect our fears that advances in science and technology will eventually lead to our destruction, physical or otherwise.”2 Ian Campell, a Professor of Arabic and Comparative Literature, argues that Arabic science fiction is an “archetypally postcolonial literature”3 since it employs the colonizer’s language, enshrined in scientific discourse, to challenge their power. Campbell expounds on how the science fiction mode usually employs an ‘explorative’ approach in which the possibility of reifying a utopia persists in the past, rather than in the future4.

Campbell argues that the utopia is often placed in the past within science fiction frameworks owing to a presumed nostalgic longing for past Arab glory5. This argument, which could be valid in certain cases and to certain extents, does not, however, pertain to all Arabic contexts- especially the Palestinian one. This is because the settler-colonial situation that dominates Palestine under the Israeli state is an extremely urgent one enshrined in the (material) present. It therefore requires material emancipation from the material state of settler-colonialism, which is located in a future time of liberation rather than a past Arab glory as in a return to ‘al-Andalus’6 (Andalusia) as a physical and metaphysical space.

Given the genocide waged against Palestinians in Gaza with the complicity of Arab states, the concept of pan-Arabism, especially for the Palestinian collective, could witness a significant rupture. Left alone to fight one of the most heavily fortified and morally bankrupt armies currently inflicting unimaginable atrocities, Palestinians’ identities will probably refuse to be included under a bigger amalgam of Arab unity in the future. This would extend to the shared ‘Arab’ dreams, in which Palestinians will not practice collective wistfulness regarding a lost utopia in the past (like al-Andalus) but instead employ the collective imagination towards a liberatory Palestinian utopia in the future. The question that arises from this approach is: can the Palestinian imagination use science fiction as a vehicle towards the reification of liberated Palestinian futures?

Images of rescuing Palestinian land are especially salient today as Palestinian land continues to be subjected to Israeli settler-colonial violence through the uprooting and burning of trees, the contamination of water, the criminalization of Palestinian foraging of their wild plants7, throwing phosphorus in the air, and preventing Palestinians from burying their dismembered loved ones deep in the ground.

Science fiction, in its broadest terms (and most imperialist applications), perhaps cannot.

To assess this, let us turn to director Larissa Sansour’s films- especially her sci-fi trilogy (in collaboration with Søren Lind). The dystopian reading of the future within science-fiction models is apparent in the three short films: Space Exodus (2009), A Nation Estate (2012), and In the Future They Ate from the Finest Porcelain (2016). In A Space Exodus, we see a Palestinian astronaut (Sansour herself) plant the flag of Palestine on a distant planet. In Nation Estate, Palestine, or the remnants of it, is transformed into a massive airport waiting room that projects images of what used to be Palestine and offers nostalgic Palestinians the chance to ‘experience’ Palestine by heating up pre-packaged traditional dishes such as mlūkhiyye8 in porcelain dishes covered with kouffiyye patterns. The dissolution of Palestinian possibility and material futures takes on an even sharper turn in In the Future They Ate from the Finest Porcelain, where eerily ethereal Palestinians, presumably dead, float around in post-apocalyptic desert spaces, trying to recount a past no longer remembered while encountering ‘relics’ of what is the present today. The future turns into an augmented extension of the present, severed from the pre-Nakba past. A dystopian image of the destruction of all Palestinian life as a future possibility continues to develop in those films.

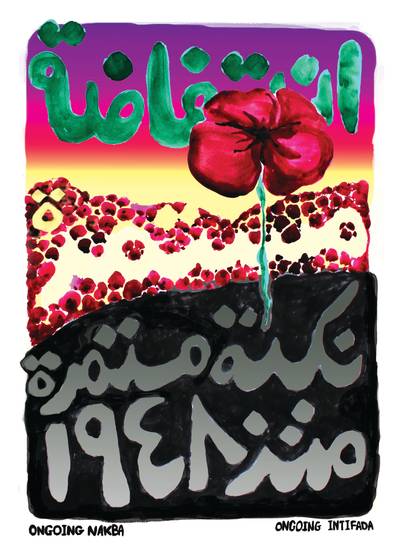

Still from Larissa Sansour & Søren Lind: A Space Exodus, 2009. Image: Larissa Sansour & Søren Lind

In Sansour’s In-Vitro we enter a minimalist futuristic hall, where a young woman and a dying woman in bed converse in low, melancholic voices. The progression of the film is interrupted by scenes showing nuclear explosions in Bayt-Laḥm (Bethlehem) as well as dreamlike images of the older woman’s memories of when she was a little girl in Palestine. The movie takes place in a post-ecocide Palestine, where some scientists (the young woman among them) plan to rescue the land by planting seeds to bring it back to life The movie ends without showing the resuscitation of Palestinian land in the future.

Images showing the rescue of Palestinian land are especially salient today as Palestinian land continues to be subjected to Israeli settler-colonial violence through the uprooting and burning of trees, the contamination of water, the criminalization of Palestinian foraging of their wild plants9, throwing phosphorus in the air, and preventing Palestinians from burying their dismembered loved ones deep in the ground.

In Sansour’s films that abide by the ‘classical’ model of science fiction to the highest of degrees, little is left for imagining alternative futures in which the worst-case scenario does not erupt. Her films present those nightmare scenarios10 as inevitable futures— ones in which all Palestinian life is annihilated. Those matter-of-fact futures are presented using the ‘classic’ science fiction tropes that utilize technological advancements in the creation of post-apocalyptic virtual worlds, replication of dead Palestinians, and the ‘preservation’ of Palestinian memory in digital worlds.

Such depictions invite us to ponder the efficacy of certain genres and modes to tell the Palestinian future. Sansour’s films present an ideal example of the debate around these futuristic genres. For example, does presenting the worst-case scenarios in the Palestinian case aid in thinking of urgent measures against the protraction of a dystopian future? Or is entertaining different possible futures, regardless of their bleakness, a privilege that Palestinians, who are currently experiencing an annihilation of their life and identity, should be able to afford? Is the replication of Western themes of science fiction, such as planetary travels, technological developments, laboratory solutions, virtual reconstruction, and digital preservation, authentic to Palestinian hope, agency, and dreams of liberation?

So as not to arbitrarily dismiss science fiction to tell the Palestinian story, perhaps a more authentic and emancipatory kind of science fiction could be utilized to tell it—one that is not enshrined in the colonizers’ dreams of occupying faraway places11. Critical, indigenous science fiction is a promising start, specifically the burgeoning subgenre of science fiction: climate fiction.

In an essay by Brigetta Pierrot and Nicole Seymour titled “Contemporary Cli-Fi and Indigenous Futurisms”12, the topic of climate fiction through the framework of indigenous studies is presented. The authors refer to journalist Dan Bloom, who used the term to describe climate change-themed speculative fiction in 200813. Often, climate fiction is not presented as “a genre in the scholarly sense but is characterized by certain formulas and conventions from different genres […] borrowing from and often embracing elements of different existing genres that go back to the sixties and were, at some point, referred to as “proto-climate-change-fiction”14. Climate fiction was coined based on a burgeoning literary phenomenon that focused on climate change and catastrophes, as well as the ethical questions that arose with it.15

Unchallenged, uncritical climate fiction, which does not incorporate the indigenous experiences of the land, is susceptible to falling into the trap of creating literature that prioritizes the prevalence of the science fiction “nightmares model” and its applications over the messages of agency, hope, and solidarity within the geographies of indigeneity.

Yet, given its origin as a subgenre of science fiction, a genre that is prone to discourses around white saviorism16, and the erasure of Indigenous experience17, climate fiction could similarly fall into this trap. According to some scholars, climate fiction tends to present climate catastrophes as passive byproducts of our times. Their critique lies in that many climate fiction texts do not delve into how climate catastrophes are directly linked to settler-colonialism, specifically classism and white supremacy18. In most presentations and applications of climate fiction, Indigenous experiences are either completely absent or appropriated. Unchallenged, uncritical climate fiction, which does not incorporate the indigenous experiences of the land, is susceptible to falling into the trap of re-producing literature that prioritizes the prevalence of the science fiction “nightmares model”19 and its applications over the messages of agency, hope, and solidarity within the geographies of indigeneity.

How does adopting the critical lens of indigenous climate fiction open more generous future possibilities for the colonized- especially Palestinians, who continue to suffer from the expansive and fatal repercussions of Israeli settler-colonialism? Indigenous climate fiction resolves this problem by incorporating, critically and expansively, Indigenous people’s experiences, histories, and associations with the land that they have inhabited outside settler-colonial and capitalistic worlds. This is especially pertinent when thinking of Indigenous agencies within these modes. How can those who have been forcefully severed from the land be righteously welcomed back to the spaces that they had inhabited for hundreds, if not thousands, of years before being “discovered” for their natural riches?

Indigenous climate fiction opens up the space for imagining (and possibly reifying) liberated futures filled with hope, agency, and fecund imaginations without freezing the currently colonized in a bleak and eternal dystopia. This can be done while reactivating their connections to the land and the physical, natural spaces from which they were severed.

Indigenous climate fiction frames the stop-motion short film Biidaaban (The Dawn Comes) by director Amanda Strong (2018). In the film, an Indigenous youth is joined by a 10,000-year-old Sasquatch (a prominent figure in Indigenous North American folklore) to retrieve the practice of sap harvesting in Ontario, Turtle Island. The short film opens with a quivering, luminous ball traveling in the forest and then morphing into an ethereal elk. Upon touching the ground, the elk turns each spot into a radiant, lively space that writhes like blood vessels or corals in fluorescent blue. The details of the contact, wherein a ball of light turns into a spectral animal capable of transmitting its magical life into the land through touch, make for an alluring visual representation of Indigenous connections to the land and concepts of return to it in ethereal forms. The mythical-cyborgish creature that guides the youth in their journey is able to pass through tree trunks and deep roots in the form of a bright, vibrant mass.

The youth in the film, accompanied by the Sasqautch and ghostly elks and wolves, participate in acts of ‘vandalism’ by drawing stencils of a bird across the maple tree trunks in their neighborhood. The youth does that stealthily, lest the neighbors, who live in wealthy, privileged houses (unlike the youth), capture the former for ‘vandalism’. At one point, the mansions nearby come to life when the water hose turns sentient like a snake and tries to rope the youth . The water sprinklers come out from the grass and start turning like blades.

These images of the defensive house, whose trees bring out their roots to catch the youth, present the foil image of the youth’s relationship to the land. That is, while the ‘vandal’ tries to return to the land through re-connecting with it, the ‘comfortable’ houses of those settling in the land, exploiting it and further subjecting its indigenous people, try to sever this connection and potential return. When the youth tries to cut the plastic tree guard suffocating the old maple trees, the plastic net wraps around them and the houses around the trees start crawling towards the youth while the ghosts of an elk and a wolf try to free them . The Sasquatch joins in, and the dawn finally comes when the youth is released. The youth presses the ground with their palm, transferring their energy to the depths of the earth, inside which we are shown three Anishinaabe people hanging in the air by the roots. The image is then inverted, and we see the Anishinaabe people on their backs, getting up and standing. The narrator, who introduces the film, ends with the note, “rebellion is on their way.” Biidaaban exemplifies a critical indigenous climate fiction in which the future belongs to the Anishinabee people through reconnecting with their land where they were killed and expelled. It draws an alternative to protracted settler-colonial futurisms in Turtle Island, in which indigenous peoples continue to be sequestered in ‘reservations’ and disconnected from their land under capitalism.

These themes are similarly echoed in Three Thousand by director Asinnajaq (2017), a luminescent movie that interweaves archival material with world-building visuals around the Inuit people. It begins with glowing vessel-like animations, similar to Biidaaban. The film starts off the English section of the narration with the sentence “my father was born in a spring igloo; half snow, half skin… I am a little Caribou woman, I will become light”.

By offering love and reverence to a land that is suffering under capitalist expansionism and extractivism, the indigenous peoples use climate fiction to heal their connections to the physical space, the land itself, and their futures on it.

The way in which images of gleaming space transform into red blood cells, thereby welding the human body and the natural space marks an Indigenous approach Throat-singing accompanies digital animations showing the metamorphosis of spacey silver masses reminiscent of futuristic aesthetics. This visual representation of Indigenous climate fiction allows a return to memory of the land and literal metamorphosis into the land as a performance of material return to it. Through that, a vast space for hope and resilience opens up; a space in which the Inuit people return to their land in the future, decades after Canadian settler-colonialism. By offering love and reverence to a land that is suffering under capitalist expansionism and extractivism, the Indigenous peoples heal their connections to the physical space, the land itself, and their futures on it through climate fiction. This is achieved in the film by interweaving archival material of the past with images of free, liberated futures.

The visual applications of indigenous climate fiction offer a rich example—perhaps a prototype—of what Palestinian climate fiction could do when employed in the visual sphere. This is especially owing to the mode’s focus on return to and reconnection with the land, employing contemporary tools to envision alternative realities, and opening space for hope and collective liberation while offering powerful images of alternative futures that do not merely protract from the settler/postcolonial present. Employing such a mode, especially within the a visual realm, is an exercise in liberatory imagination at collective levels. Applied to the Palestinian case, critical or indigenous climate fiction can escape the potential dystopias, fragmentations, and hyper individualization that often recur in passive science fiction. It also shows how present-day technologies and digital collectives could participate in liberatory thinking and reification of alternative futures. Critical climate fiction can therefore be added to the toolbox of liberatory imagination and reification of Palestinian freedom in the present and in the multiple futures currently in formation.